In a 2014 Guardian article about the sharing economy, writer Evgeny Morozov wrote: “…there is nothing to celebrate here: it’s like handing out everybody earplugs to deal with intolerable street noise, instead of doing something about the noise itself”. Is it the same for digital social innovations (DSI)?

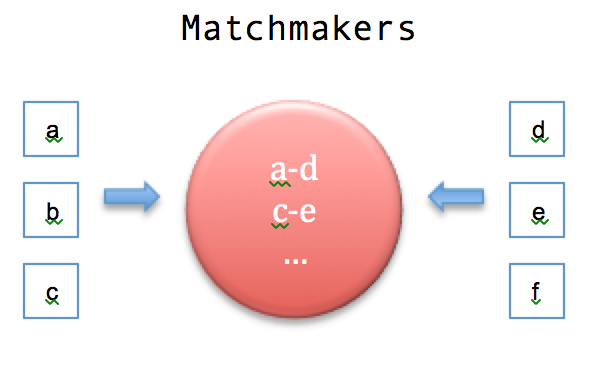

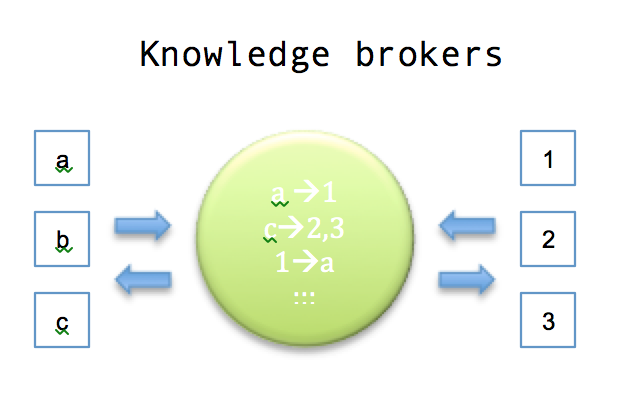

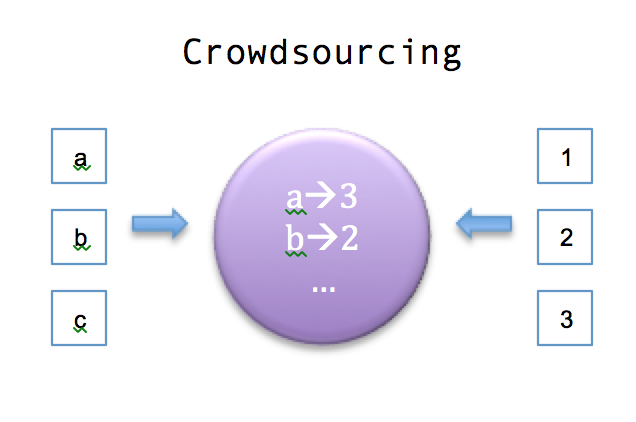

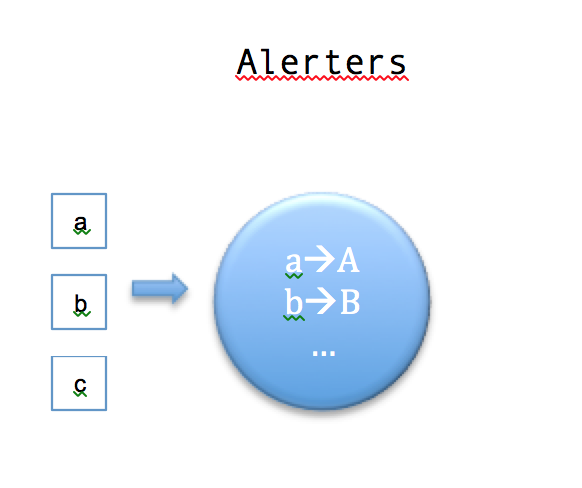

DSIs empower civil society by enabling exchange and sharing of resources and information on digital platforms. For example the beTobe network matches individual volunteers with non-profit organisations, CALM by SINGA platform in France matches refugees with local hosts. The crowdfunding platform Humaid collects funds for disability projects, while the I Wheel Share platform collects data on accessibility conditions in real spaces.

Ideally, a transformative innovation is a game changer; it brings about systemic change that solves a problem at its root, rather than providing ex post solutions effective only in the short run. Sadly, most DSI cases seem far from being game changers in this sense, but rather provide temporary relief in the wake of a severe economic crisis and in the face of deepening environmental and social problems.

However, given the vast advantages of increased speed and scale of interactions enabled by ICT, DSIs can fulfil their transformative potential. This highly depends on their efficacy in helping civil society and communities to construct and formulate problems, in bringing these problems into public arenas, in enhancing their perception of their own agency, and in engaging a broad variety of stakeholders in finding solutions. For this to happen, there are at least three obstacles, however.

Obstacle 1: Survival and autonomy

Most DSI platforms have problems with sustaining themselves to ensure their survival and autonomy in the long run. Non-profits often have fund raising and resource access problems and rely on donations. Those backed by a parent non-profit (or for-profit) organisation, often rely on complementary activities of the parent, which makes them dependent on the latter. Some other business models in for-profit cases are based on commissions from users, premium payments, or commercialising data of users, which cause privacy problems. These business models can be in tension with the social mission that their existence relies on. Therefore in the long run they can turn into mainstream for-profit enterprises.

Obstacle 2: Digital literacy and civic engagement

According to recent data on digital economy and society in Europe, 85% of people have internet access. But digital inclusion goes well beyond mere access and concerns questions about what people do on the internet when they are connected, which depends on socioeconomic variables and geography. The most common activities in Europe are sending and receiving e-mails, finding information, social media and online shopping. And some studies show that those who are active in civic platforms are the ones who are already active in volunteering or other civic society activities, raising concerns about the extent to which DSI can truly bring about structural change.Moreover, according to studies, participation in open platforms like Wikipedia also depends on a range of socioeconomic variables, clearly pointing to persistent exclusion of certain groups or geographies in engagement. The digital society landscape is still far from being truly inclusive and egalitarian.

Obstacle 3: Lack of cross-sectoral networks

A third problem is the lack of enduring networks between different stakeholders contributing to social and environmental progress. Digital social innovators seem to be cornered in digital bubbles, in niche sectors supported and fed by specific ecosystems where contradicting interests prevail. Most of these networks originate from the digital sector, rather than sector-specific experts in related problem areas. The existence of bridging organisations that could serve as intermediaries between different stakeholders is critical, but weak. For example in France, national digital think thank Conseil National du Numérique does not address social and environmental issues, and neither does the digital cluster Cap Digital, reinforcing the isolation of digital networks from specific sectors concerned.

Whether these obstacles will be overcome in the future remains to be seen. The transformative power of DSI also depend on which sectors they address, but these three obstacles seem to be critical for all of the sectors concerned.